Anxiety is a horrible feeling that can leave people feeling overwhelmed and crippled by its power. It is one of the most common reasons people come to therapy.

However if you want to beat your anxiety – it really helps to understand how anxiety works in your brain. If you can understand what your brain is doing, you are better equipped to change your brain.

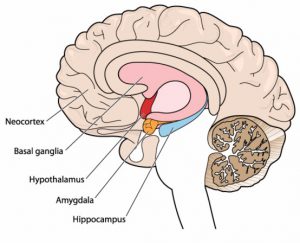

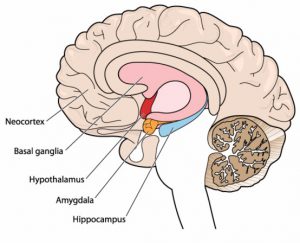

First of all – some basic brain facts need a diagram:

In this diagram the lighter coloured, outside part of the brain is the cortex. It’s the ‘grey wrinkly stuff’ most of us think of as the ‘brain’. This area controls the ‘higher functions’ of language, thinking, planning and problem-solving. This part of the brain uses language and has a concept of time.

The coloured sections of the brain (eg hypothalamus, amgydala, hippocampus) make up a very important part called the Limbic system. This area functions through emotions and body sensations. It is responsible for rapid responses to help us stay alive and function. This includes pleasurable responses, but specifically in relation to anxiety, it also kicks in during times of stress. It controls the ‘fight, flight or freeze’ responses when we are in danger.

Both parts of the brain play a role in anxiety and, unless we treat both, anxiety remains lingering in our lives.

The Cortex is the area most people are thinking about when they think of anxiety. This is the section of our brain that worries, over thinks things and may ruminate when we are anxious. Traditional therapies such as CBT can help treat this aspect of anxiety.

But sometimes therapists overlook the Limbic System. I call this “amygdala anxiety”. This anxiety is characterised by vague feelings of uneasiness, a sick feeling in the stomach, even when there is no obvious danger. You may feel like your anxiety doesn’t have a specific, logical cause but it hangs around anyway.

The cortex causes the thinking symptoms of anxiety, but the amygdalae (we have two of them in the limbic system) are responsible for the other horrible symptoms: sweaty palms, pounding heart, rapid, shallow breathing, tense muscles and upset tummies.

The cortex and the amygdalae talk to each other and reinforce the anxiety. For example, fast breathing and a pounding heart sends a message to the cortex that the body is in danger. This sets the cortex off on a round of frantic worry! Unless we treat both the cortex and the amygdala, anxiety is likely to continue.

It is also important to realise that the Cortex and the Amygdalae operate on completely different timetables. Any treatment needs to take this into account. The cortex is slower, but the amygdalae’s rapid response – geared to survival – can throw you into a panic well before the cortex has time to sort out fact from fiction.

An example to illustrate: If you were out bush walking and you saw a stick that looked like a snake, you might gasp and jump backwards. Your heart will pound and your breath will come in short sharp pants. This is your limbic system (eg amygdalae) working. Then you look again, your brain realises it is a stick and computes: stick= harmless = calm down. This is now your cortex talking. It might run late, but it’s helpful!

However the amygdalae can also override the cortex. A typical example will be someone who had childhood trauma. These people will have over-active amygdalae – they needed this to survive childhood. However as adults, even though a logical rational part of their brain will know the danger is over, their amygdalae will keep on red alert, constantly sending danger signals to the cortex. This can also happen for people who just had an ‘innate anxiety’ as a child, even without an obvious trauma. For these people their overactive amygdalae keeps triggering the cortex to worry.

Treatment

The good news is your brain can be re-wired!

So how do we treat anxiety to make sure BOTH parts of the brain are calmed?

Treating Amygdala Anxiety

Specific treatments are needed to calm the amygdalae to make sure they stop sending inaccurate danger signals to the cortex. If we do this we can ‘get in first’ and get on top of anxiety. To treat amygdala anxiety we have to understand that the amygdalae don’t have words or a good sense of time. The amygdalae can only learn through body sensation and body action. Examples include:

- Grounding exercises;

- Breathing exercises to encourage a slower and deeper breathing;

- Muscle relaxation;

- Starting practices like meditation, yoga and tai chi;

- Developing a great understanding of amygdala triggers (a therapist may be necessary for this explorative work);

The next most important things to remember is that the amygdalae don’t learn by people (you, or someone else) just speaking to them. They can only learn through experience. Therefore it is vital that the amygdalae get new experiences. For example if someone is so scared that they are afraid to go outside then the amygdalae never get a chance to learn that the outside world is mostly pretty safe. Every time the fearful person avoids the outside world the amygdalae get a mental ‘pat on the back’, a reinforcement that they are doing the right thing. Next time they continues doing the same thing, in an even stronger manner!

HOWEVER if that person gradually tests going outside and realises they are safe the amygdalae get to learn that the outside world is safe. The same applies to all sorts of fears such as bugs, public speaking and night time. An important part of beating anxiety is pushing through the fear barrier to teach the amygdalae about safety. As already said we can’t do this with words alone – as the amygdalae just can’t ‘hear’ them.

Some people refer to these as ‘exposure therapies’ but I don’t think this is a soothing and useful expression. The thought of being ‘exposed’ is enough to make most of us anxious! I would rather think of them as ‘practicing new activities’ or ‘giving your amygdala a new experience’. A therapist can help guide you through a gentle and gradual program.

Treating Cortex Anxiety

Once amygdala anxiety is reduced the cortex is less triggered, but it is still important to work on cortex anxiety. This is done through strategies such as:

- Reminding yourself that your cortex is not always right. Develop a healthy scepticism about thoughts. Develop the ability to notice them, analyse them and choose a response, rather than immediately reacting;

- Identifying unhelpful thoughts;

- Developing more rational thoughts and arguments against unhelpful thoughts;

- Using programs such as ‘Wise Mind’ strategies; and

- Using mindfulness and thought de-fusion to combat worry and rumination.

Getting More Help

Anxiety can be a very entrenched problem and be hard to shift. However it is possible to re-wire the brain. A useful self help book is: Rewire your Anxious Brain by Catherine Pittman and Elizabeth Karle.

Sometimes people find it helpful to see a mental health practitioner to get support in reducing anxiety symptoms. A counsellor, psychologist or mental health social worker may be a great help in getting on top of anxiety using a ‘whole brain approach’.

© Kate McMaugh Psychology, 2017